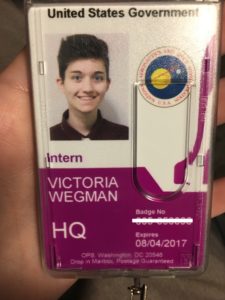

Alumni Spotlight: Victoria Wegman ’15

Victoria Wegman graduated from Blackhawk High School in 2015 and studies Communication Analysis and Practice at Ohio State University. She interned at NASA in the summer of 2017.

Victoria Wegman graduated from Blackhawk High School in 2015 and studies Communication Analysis and Practice at Ohio State University. She interned at NASA in the summer of 2017.

JT: I’m at once surprised and not surprised that you interned at NASA this summer. Knowing you in high school, I remember your decision being between music and physics. Yet your internship at NASA centered around your major, which is now communications.

VW: I think I’ve always been a fairly well rounded student, interested in most of my classes. The big issue for me was not wanting to go into liberal arts.

Why not?

Because I had that complex of thinking it was easier and less worth my time than, say, engineering or the hard sciences. Plus, music has always been a passion. I was in the [Blackhawk] Music Academy for a short time, and I always thought music would be a great passion to pursue, but not a viable career option.

How much of that was you, and how much of that was external pressure to make the “smart decision”?

Freshman and sophomore year, that was all external because I was dead set on being a music teacher or a professional performer. But I was still learning about what it actually takes to get into that field. I learned about who I am and what my strengths are; I also learned that being a music teacher is not something that I would be a good at or necessarily enjoy. It was a hard thing to accept, but I accepted it in my junior year.

But you haven’t abandoned music.

Yeah, I’m in the jazz program as a non-major. I broke my collarbone so I missed the auditions, but I’m working toward getting back into an ensemble. I play my guitar every day, but with saxophone, it’s hard to play without an ensemble. At Ohio State, you can easily get into any of several bands they have. In my freshman year I joined a jazz ensemble, playing traditional jazz. Then I auditioned to get into one of the big bands; I made it, and now I’m a member of the Jazz Workshop Ensemble big band.

Were you well-prepared, having studied at Blackhawk?

[At Blackhawk] I definitely got a sense of what I was going to be when I auditioned for the PMEA Bands, specifically the jazz band, because that’s what I was most interested in. I had an idea how good other people were at my age, where I fit in, what my strengths were. I also found that I actually wasn’t that good at, for example, soloing, so that was something I had to accept and work on to play in such a reputable music program at Ohio State.

How did your college search play out?

I was set on going to Duquesne or Carnegie Mellon until the summer before my senior year, when it boils down to where you’re going to visit and where you’re going to apply. I did a program at Carnegie Mellon called “Engineer for a Day” and I hated it.

Really? Why?

I loved the campus but I hated the actual stuff that we were doing. I was entirely uncomfortable and those around me were not fun to be around. I just didn’t feel a place for myself there.

How were they not fun?

Really intense people who were too intelligent to have a conversation. They were just so focused and so good at the physics and mechanics that they weren’t able to function socially, which is a huge issue in engineering in general.

In your experience, how is the gender breakdown in engineering? Is it still a heavily male pool of students, or are we moving more toward gender equity?

We are quickly moving towards equity. This year at Ohio State, there were more women accepted in the computer science engineering program than men, which is the first time it’s ever happened. It was still like 52% versus 48% which, you know… equitable! But before it was close to eight percent.

So I guess the most ironic – or counterintuitive, or you pick the adjective – element to your story is this: You had to quit physics to work at NASA. How does that happen?

I was in honors engineering, which is not difficult to get into at Ohio State, but it’s difficult to maintain. I should not [have enrolled in honors engineering]. It’s my first regret.

Why?

You don’t need to be in the honors program in college. There are so few actual benefits. I have not had any potential employer care about whether or not I’m in the honors program. It’s all about GPA and coursework and the cover letter. Oh my gosh, the cover letter.

Why is the cover letter so important?

That was the number one reason I got a job at NASA: I was able to write a good cover letter.

So what makes a good cover letter?

Showing you have the passion for the job. It was a way to explain my career goals – that’s the career path I want to take, but I know I’m not there yet. I was coming up against graduate students, but I was a lifelong fan of NASA and it was definitely a career path that I wanted to pursue. My cover letter was essentially how my “well-roundedness” – my music path in high school, plus a year in engineering and a year in communications – wasn’t enough to get me in a great place to have this internship. So admitting that I was undoubtedly unqualified compared to other candidates, but expressing that I had a passion and drive and proven skill to succeed, really got me that internship.

Plus, in communications, every writing you put out there is basically a meta-resume. All of your writing is a writing sample.

Yes, absolutely.

So what convinced you to leave the honors engineering program and pursue communications?

I was suffering in engineering. I was not necessarily considering leaving because I didn’t know who else I could be. I still loved all my courses except calculus, but who actually likes calculus in college?

Ethan Frederick. Only Ethan Frederick.

Yeah, true. I took AP Calc AB in high school; I got an A and did not struggle in that whatsoever. I took honors calculus in college and I straight-up failed it.

Really?

I did. I had to get grade forgiveness because I got a D- and I tried my absolute hardest. It was devastating and completely unexpected that I took the exact same course — just at a college level — and I failed it.

How did that feel? That was the first that had ever happened to you, right?

Yeah, the only course that I actually struggled with in high school was AP Chemistry, and even then I managed to get a B. I wasn’t spending multiple hours a day to work that hard – it was just the first time I had to study for something and maintain an OK grade. Looking back, AP Chemistry is the course I took in high school that most prepared me for college – especially hard sciences in college. If you were to tell that to me four years ago, I could not have believed it. I really struggled with the way that course was set up. But that’s generally how it was for all hard science courses in college so far.

So what did you do?

I took a step back and dropped out of the honors program, except for my core engineering course, where we basically learned how to build a robot.

Wow. What kind of robot did you build?

Everybody had to build a robot that completed specific tasks. At the end of the year, we competed to see who could complete the tasks most efficiently. You also got bonus points and cash prizes, but they didn’t tell us about that [in advance].

How did you do?

We got second place out of 76 teams in documentation, which I spearheaded. We got first place in design. We got 68th in efficiency because our robot failed. We also got first place for website design. That was something that I was able to put on my resume, saying that out of all the students [participating], my parts in the project were number one and number two.

So your engineering expertise wasn’t in engineering.

That’s it. The communication side of it. That should have been a red flag – or more like a green flag, right?

Right.

So second semester, freshman year, I got into a course with the president of the university, Dr. [Michael V.] Drake, [studying] civil rights. Eighteen honors freshmen were picked to take this course.

So finally there’s a benefit to being in the honors program.

Yes, that is the one thing that I enjoyed coming out of the honors program, the one benefit that I had. It doesn’t boost your GPA, like it does in high school with the APs. You don’t get preferable housing. You can schedule earlier than non-honors students; however, that did not affect me after I dropped honors. So there’s no true benefit other than if you’re one of the 18 people that is picked to be in the civil rights course.

So we often talk about the networking benefits of a school-within-a-school model, but it’s also good luck.

That’s true. In the civil rights course we had to do a lot of in-class discussion, which I loved. I loved that in high school, too, especially with AP Literature. But I also had to write a lot. It was a lot of text-based material, going back to “talking to the text” and all those sorts of skills I learned at Blackhawk.

That’s good to hear. We are renewing our emphasis on those techniques at the high school.

And I didn’t have that at all in engineering. So Dr. Drake wasn’t the only instructor for the course; it was a team of high-ranking instructors, including the dean of the law school, Dr. [Alan C.] Michaels. He’s a big name in the legal world. They’re still these untouchable people, like the dean of the law school and the university’s president.

Completely. That’s amazing that you had that level of access.

I know. And we’re having these in-class discussions. So [Dr. Michaels] came up to me at the end of one of our sessions – which was unexpected, because I was not intending to network with him because I still have no interest in going to law school – and he said, “I really think you should consider not being an engineer.” I hadn’t even mentioned at all that I was struggling in engineering.

How did you respond?

I was at first taken aback. I actually asked, “Why? What do you see?” He said, “You have a lot of great ideas that are not connected to engineering. You have a passion for things that are not engineering. I see a future for you in, say, communications. I think you should seriously consider law school, [maybe being a] civil rights lawyer. Give it some thought and we’ll talk about it next week.”

Did you?

Well, now we’re in the second half of course. I talked to the other students and asked, as humbly as I could, if they were getting the same amount of individual attention.

That’s a tricky road to walk.

Yeah, I know. All of the instructors – including President Drake – had individually emailed me saying that I should seriously consider not being an engineer and pursue something related to liberal arts.

Was that hard for you to hear? I know that your repeated success in the hard sciences was tied to your identity not just as a student, but as a person.

At some points, yes. But I knew in high school that I was good at writing. I did well in TSA, and I excelled in it, and did especially well in AP Language with Mr. McCowin. I never disliked writing, whereas most people around me hated the timed essays. I saw them as challenging and fun. But I needed those high-ranking instructors to show me something I couldn’t have recognized in myself.

Plus, it sounds like you hated engineering, or at least hated the amount of work you were putting in to not get the payoff.

It didn’t make sense to me. I worked myself into more than one mental health crisis. I was sent to the hospital more than one time because I was so sick. I was suffering a great deal, and it wasn’t worth it. That’s something I had to really come to terms with: being an engineer is not who I am.

I think that, as a major, communications gets a bad rap. A lot of people think it’s what people choose when they don’t know what to major in, and that’s not necessarily the case.

That is the case for some people.

But not for you.

Yes, for me it was truly the logical choice. I am thrilled with my major. There is not a single part of communications that I don’t like.

If you’d have told the 2013 edition of Victoria Wegman that you’re going to be in communications and you’re going to love it, what do you think that version of yourself would say in response?

I think about that every single day.

Really?

I do. I would’ve laughed at myself, I would’ve asked, “How in the world is this me?” Yet I have loved every single communication course I’ve taken. It’s truly the right fit for me.

How would you describe the benefits of attending a big school like Ohio State?

Even I had not been fortunate enough to be one of the 18 people in that civil rights class, I would have found my niche anyway. Not a single person I have talked to — I’ve had to talk to a lot of people as an RA — nobody feels they’re a small fish in a big pond. No one I’ve met feels lost in the crowd here. Everybody knows somebody. Networking is fantastic. The opportunities here are endless. We bring in big names, big speakers, great internships…

So this was a big summer to be working at NASA.

Yeah it was. Everybody who actually worked there said I could not be there a more interesting time. Especially because I got to work with [White House Communications Director Anthony] Scaramucci, and what that was like for, you know, nine days. But going in, I was terrified.

Why?

I don’t like change, but I knew this change was necessary. Plus, I was putting it up so high, such a necessity for my career to take off, that I was putting too much pressure on myself. I mean, it’s NASA.

What was it like to work for a government agency in the current political climate?

NASA is strange in that it has so few appointees on staff; about half of the employees are contractors. Most of the people I worked with in the science communications department were contracted from public relations agencies. But with the political climate, wow. Every day, everybody has to have the news on, at all times, or you’re not going to be able to do your job well.

How did that affect the work environment?

You have to be as respectful as possible, making sure you’re balancing your job and serving your country. When you’re serving your country, you actually have to serve the President first, especially in this administration. I was hard-pressed to find someone who was actually adamant about serving this president.

What did that look like?

The administration was not helping NASA employees do their jobs, especially in the climate change department. I had to work a lot with science communicators whose job it is to talk about climate change.

Everybody thinks of the EPA as the government agency tied to climate change, but NASA was assigned that role as well.

Right. The EPA is the agency that can do something about it; NASA is the agency that explains and studies it, less from a policy standpoint and more on research. Then the Executive Order at the beginning of the summer when like Rogue NASA and Rogue National Parks –

Right, I remember that –

– that all sprung from the Executive Order saying that the government could no longer talk about climate change. That is a huge deal at NASA because that is a lot of what NASA does. I saw that firsthand because I was not allowed to talk about climate change.

It’s like you were running two separate channels.

Yes, especially as someone who did mostly social media I had to watch what I was putting out at NASA. It was quite a balancing act.

Wait, you had the password to NASA’s Twitter?

Yes.

Nice! What is it?

[Laughing] I don’t remember. It was really convoluted. I ran the NASA history accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr. I did that every day. I contributed to the flagship NASA accounts. This summer, I basically talked to millions of people. That was incredible.

It’s got to be crazy that you type something and it’s like… That’s a big microphone.

Yeah! This summer, I talked to Ted Cruz, Mike Pence directly…

Were you the one who told him to touch the thing it said not to touch?

I was the one who helped him turn it into a meme. That’s what I directly talked to him about. I was in the room on a conference call with him how to handle that photo.

Really? Tell me about that.

NASA was who published that photo. The conference call was talking with the Vice President’s office on whether or not we should publish the photo.

Because you knew it was going to go viral?

Yes, but we were the only [organization] to have that photo. My really good friend Emily – she’s the youngest person on the social media team, which is just three people who run all of NASA’s flagship accounts – Emily is like 26, and she used to work for Obama, and then when Obama left she went to NASA. Emily took that photo. So she got on the conference call with me, the director of communications at NASA, the assistant director, Mike Pence, and Mike Pence’s chief of staff.

That’s so cool.

So we’re saying, “We have to publish the photo.” It would be restricting information if we didn’t, because it’s something public that happened, and it’s pretty funny. Emily was like, “What if we meme it?” I was laughing in the corner, trying to not seem as young as I am. And the communications director is a Trump appointee, so it was complicated.

Sorry @NASA…@MarcoRubio dared me to do it! pic.twitter.com/qIYtKOPyFh

— Vice President Mike Pence Archived (@VP45) July 7, 2017

How did the picture get published? Did Pence have to clear it?

Yes, his chief of staff was the person that said we could publish it. We don’t want to make the vice president look bad, so the chief of staff and the director of communications [for NASA] gave the OK, as long as we would spin it.

It was OK to touch the surface. Those are just day-to-day reminder signs. We were going to clean it anyway. It was an honor to host you! https://t.co/gu8zxknsJv

— NASA (@NASA) July 7, 2017

What an experience.

Yeah, following politics, I was always thinking, “I’d love to be in the room when that happens.” The biggest takeaway from that was being able to be in that room if I wanted to. It’s crazy.

And you were published already.

Yes, in the NASA quarterly newsletter, which goes out to subscribers. It was an article about five notable eclipses in NASA’s history. Everything that NASA publishes is in the public domain, so it was immediately posted to NASA.gov.

Do you have time for the lightning round?

Sure!

Any podcast recommendations?

StarTalk Radio [Show by Neil deGrasse Tyson], of course, and Stuff You Missed in History Class.

How do you get your news?

CNN.

A movie you love, but that nobody talks about.

The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Number one snack for a road trip?

Twizzlers.

Last book you couldn’t put down?

Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson. It’s about how he tried to get people off death row. He’s still a working lawyer.

Your favorite room at Blackhawk High School?

Ms. Underwood’s, or Ms. Biega’s.

Favorite movie death?

I want to say Han Solo, but for comedy’s sake I’ll say Javert in Les Mis, because Russell Crowe can’t sing.

Finally, what’s one piece of advice you’d give to current students at Blackhawk?

If you get any sort of exposure to people with different worldviews, listen to them.