“You remember the one gleam of jollity that shot across our dismal sojourn in the rain and wind of Angels Camp.

I mean that day we sat around the tavern stove and heard that chap tell about the frog and how they tilled him with shot.

I jotted the story down in my notebook that day and would have been glad to get $10 or $15 for it — I was that blind. But then, we were so hard up.

I published that story and it became widely known in America, India, China, England; and the reputation it made for me has paid me thousands of dollars since.”

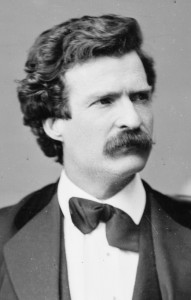

-Mark Twain, 1870

On the way to Angels Camp, you strike up a conversation with the boatman, who tells you about life as a riverboat pilot on gold country. His stories fascinate you — rich fatcats with trunks full of silver-plated flatware, Chinese laundrymen, mad scientists and mountain men, opportunists carting dozens of jugs of liquor.

Once you get to the diggings, you find your mind wander not to your potential riches, but to life on the water. After a few sizable strikes, you buy a small riverboat yourself, and begin ferrying passengers from San Francisco and Sacramento out to the camps.

When the war comes in 1861, the army closes the river to all unnecessary traffic. You take a job at the Angels Hotel doing odd jobs and tending bar throughout the war years.

You’ve always been a good listener, and that skill continues to pay off behind the bar, just as it did on the riverboat. Keeping your mouth shut is especially beneficial during wartime, when your customers may have conflicting allegiances.

On a cold, wet night in February, 1865, as the war winds down, you’re throwing split cedar into the wood stove when the door blows open. Three young men shake off the cold and pull up to the bar.

Two of them are the Gillis brothers, both great storytellers, and the third is a fellow with a bushy mustache who introduces himself as Samuel Clemens.

The men nurse toddies to fight the winter chill, reminiscing about early days in the diggings. Clemens tells a tale about his days as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi, and your ears perk up.

“I was a boatman myself,” you say. “Hauled a lot of 49ers.”

“Is that right?” asks Clemens. “What’s the best story ever told on your decks?”

You tell Clemens an old California tall tale you’d heard a dozen times, about a fellow named Jim Smiley and his world champion jumping frog, which he carried around in a box.

“One day a stranger told Smiley that the frog didn’t look so special,” you recall. “Smiley says I’ll bet you fifty dollars he can out-jump any frog in Calaveras County. Stranger tells him to find a frog, and it’s a bet. While Smiley’s out looking for the frog, the stranger fills up Smiley’s frog with birdshot. Smiley’s frog couldn’t even get off the ground!”

The men break into broad laughter, which continues for several minutes, ending with Clemens teary-eyed and Jim Gillis in a coughing fit. The men tip well and leave.

You think nothing of your encounter with Samuel Clemens until, a year later, you read Clemens’ version of your story in the San Francisco Call. Clemens — now known as Mark Twain — soon becomes the most popular writer in America.

But as you tend bar for decades in Angels Camp, it turns out that you have the most interesting story of all.

Click here to play again